Let us assume that you are not an Accounting & Finance professional, but you want to evaluate a proposed Investment Plan. You don’t know a method to do it, and you have found out that there is no relevant article in Wikipedia (as discussed in a previous article). You have asked for the opinion of many seasoned professionals and you have read several books on the subject. However, in both cases, you got a complicated and rather incomprehensible answer, that has left you more mixed up than you were before you started.

Eventually, you have given up hope that you can get an answer that you can understand. Then you decide to do something radical. You ask the “average Joe off the street” how he would evaluate an “Investment Plan”. The answer that you are most likely to get, will probably look like this:

- With this hand, I take “X amount” out of my pocket, and I give it, so that the new investment can be created.

- With the other hand, throughout the years, I receive “Y amount” from the new investment.

- I compare the “amount that I give” with the “amount that I receive”.

That’s the kind of answer that you’ll probably get from the “Average Joe off the street”. The only comment that I can make about it, is that there’s not a single thing in it that’s wrong. All of it, is 100% on target. Bullseye.

So, now that we have found a way (that is understandable and makes sense) to evaluate an investment, let us try to implement it, on a practical level. My first reaction to that will probably be: “Not so fast. The theory might be simple, but the implementation is not”.

There are two values that we must calculate: “what we give” and “what we receive”. The “give” part is usually the most easy to establish. In the most difficult scenario, the equity will be contributed in two or three installments, or the investor will also contribute the use of a building or of a truck etc. The complicated value is the “receive” part.

First of all, let us understand what the investor does not receive. He doesn’t receive:

- Every individual cashflow that will take place (collections and payments). That might be the basic idea behind NPV and IRR, but the truth is that it has no connection to reality.

- “Earnings of Year 1”, “Earnings of Year 2” etc.

These are two notions that have created tons of confusion and must be scraped and forgotten ASAP.

What the investor really does receive is the following two things:

- Incremental payments, such as dividends, withdrawal of equity etc, on the basis of the actual payment date.

- The residual value of the investment, on the basis of the last day of the “Investment Evaluation Period”.

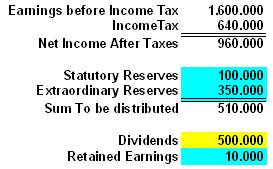

Let us make the assumption that in the created company, for “Fiscal Year 1”, that lasts from “Jan 1 2012” till “Dec 31 2012”, we have calculated (and not forecasted, as discussed in a previous article) that it will have “Net Earnings before Taxes” of 1,600,000. This is not what the investor will receive. The breakdown might look like this:

The investor will receive the dividends (500,000) on the date that they are actually paid (for example: on July 17 2013). The sums of the “Statutory Reserves”, “Extraordinary Reserves” and “Retained Earnings” are monies that are not distributed, but remain inside the company. They add up to the company’s residual value at the “End Date” of the “Evaluation Period”. Their sum, on some days:

- Increases the positive “daily balance” of the Bank account, which results in more “Interest Income” (for example: at 0,50%)

- Decreases the negative “daily balance” of the Bank account, which results in less “Interest Expense” (for example: at 6,00%)

- On some days, it is the deciding factor that turns a negative “daily balance” of the Bank account (source of “Interest Expense”) into a positive “daily balance” (source of “Interest Income”)

The same effect, applies also to the dividends, until their payment date. Any accurate calculation method must be able to incorporate the above effect into the calculated final result. In previous articles, we have seen that this can never happen thru the NPV and the IRR methods.

The investor also receives the residual value of the investment (i.e. the valuation of the new company) at the “End Date” of the “Evaluation period”. That is the combined total of the following values:

- Balance of the Bank account

- Valuation of residual stock of Goods (products, merchandise, raw materials, packaging materials etc)

- Payments that will happen after the “End Date” of the “Evaluation period”, but are an integral part of it. Examples are: Payment of VAT for the last month, Payment of Income Tax for the last “Fiscal Year”, Payment of Dividends for the last “Fiscal Year”, outstanding payments to vendors etc

- Collections that will happen after the “End Date” of the “Evaluation period”, but are an integral part of it. Examples are outstanding collections from customers etc

- Market (resale) value of the existing equipment, buildings, cars etc

Only the last (fifth) category of values is a matter of forecast. The first four categories should always be the product of a calculation.

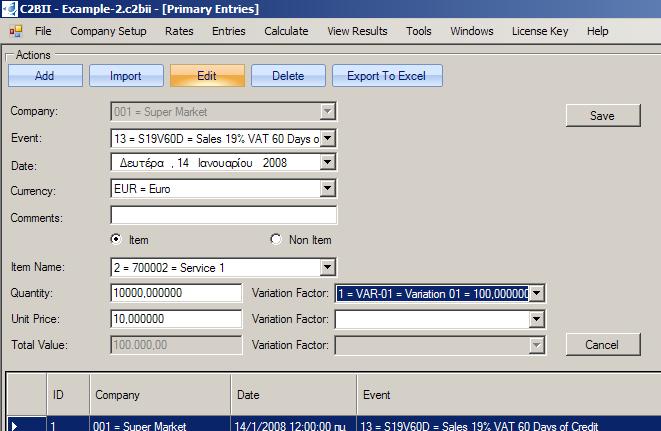

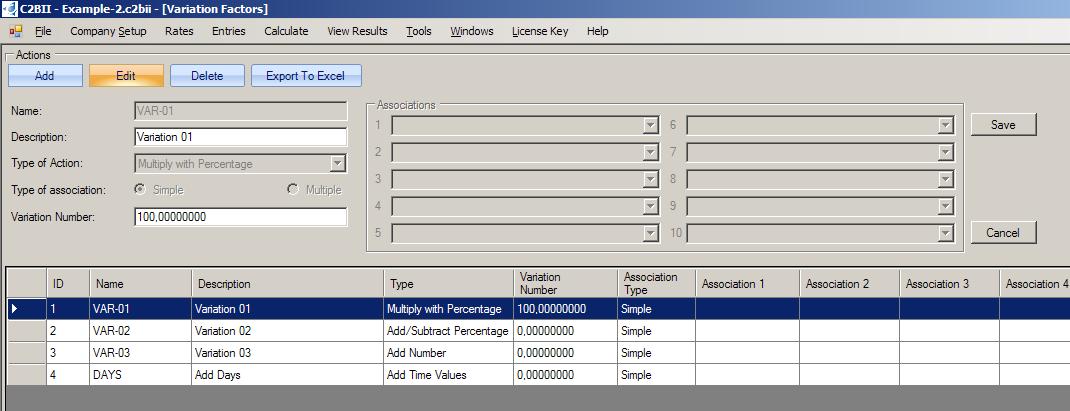

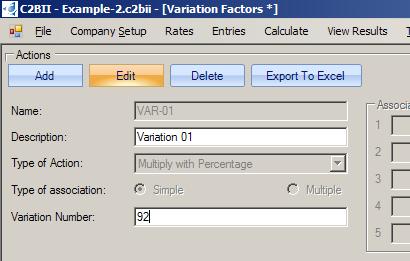

Stick around, as we are going to see how all this, is being handled by C2BII in a way that is easy to understand, implement and verify.